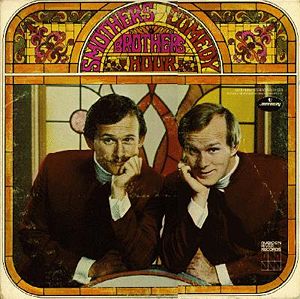

I was in high school when The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour was on TV. Every Sunday night, Tom and Dick mixed music with political satire, and for the first time, I realized that jokes about presidents weren’t just late-night silliness.

Humor was a way to question the Vietnam War, civil rights, and the powers running the country. The Smothers Brothers were relentless. They invited George Segal to strum his guitar and sing The Draft Dodger Rag, with the brothers, a jab at the Vietnam War.

That was also when I caught the campaign bug. I started collecting political memorabilia during the 1968 election: buttons, bumper stickers, pamphlets, you name it.

Back then, campaign buttons were serious business. They weren’t ironic or clever; they were straightforward: “Nixon’s the One” or “Humphrey/Muskie ’68.” You wore them to declare your allegiance.

Pop culture turned buttons into little billboards of wit, protest, and rebellion. “Save Water, Shower With a Friend.” “Make Love, Not War.” “Lick Dick in ’72. – I Am Not a Crook.” Those were the short and sharable analog social media memes of the day, designed to shock or amuse, and passed from person to person like viral content before the internet existed.

Politics was alive in my household, too. The first presidential race I remember was 1964: Mom voted for Lyndon Johnson, Dad backed Barry Goldwater. We didn’t talk politics over teriyaki chicken.

By 1972, I was finally old enough to vote, and I cast my first presidential ballot for Richard Nixon, which I now regret. At the time, I thought I was joining the “silent majority.” What I didn’t realize was just how much Nixon despised being ridiculed.

If comedians poke fun at celebrities or everyday people, they risk lawsuits for defamation or invasion of privacy. When the target is a politician, the rules shift. Public officials are held to a higher standard, and satire is one of the strongest forms of protected speech under the First Amendment.

This principle was reinforced by the 1964 Supreme Court case New York Times v. Sullivan, which held that public officials must prove “actual malice” to win a defamation case. That means comedians, cartoonists, and satirists have wide latitude when mocking political figures.

Two presidents of the late 1960s, Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, illustrate how differently politicians can react when they become the butt of a national joke.

Johnson: Laughing in Public, Fuming in Private – On the surface, Lyndon Johnson looked like a good sport. When the Smothers Brothers sent him a letter apologizing for poking fun.

“It is part of the price of leadership of this great and free nation to be the target of clever satirists. You have given the gift of laughter to our people. May we never grow so somber or self-important that we fail to appreciate the humor in our lives,” he replied with words that sounded downright noble.

That sounds like a man who could chuckle at himself.

Behind the scenes, Johnson was anything but amused. He reportedly phoned CBS president William Paley, demanding, “Get those b@st@rds off my back.”

Despite the show’s popularity, CBS abruptly canceled the show in 1969, allegedly because scripts weren’t submitted in time to be reviewed by the censors. The brothers sued, won close to a million bucks in 1973, and cemented their reputation as countercultural heroes. They were effectively blacklisted from TV.

LBJ wasn’t humorless. He leaned on his Texas storytelling whenever he needed to break the tension. He’d spin long, folksy yarns in his Hill Country drawl, throwing in barnyard jokes and crude punchlines. He poked fun at himself after gallbladder surgery, joking with reporters that if they didn’t like seeing his scar, maybe he’d show them something else instead. He posed with his beagle, lifting Him up by his floppy ears. Johnson’s humor wasn’t polished or TV-friendly, but it worked in private and kept people off balance and under his control.

Nixon: The Image Makeover That Didn’t Stick – Nixon didn’t just dislike satire. He treated it like an enemy operation. Reports say he even hired a private investigator to dig up dirt on the Smothers Brothers.

At the same time, Nixon knew he had an image problem. He was seen as stiff, awkward, and humorless. So during the 1968 campaign, he made a surprise appearance on Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In.

“Sock it to me?” was his short, awkward, and unforgettable line. For a moment, it worked. People laughed with him instead of at him. It was a PR masterstroke, the equivalent of today’s politicians appearing on The Late Show.

His charm offensive didn’t last. No comedy cameo could paper over Nixon’s deep paranoia and hostility toward critics. The same insecurity that made him lash out at satirists eventually unraveled his presidency in Watergate. All the jokes in the world couldn’t save him from resigning in disgrace on August 9, 1974.

Why It Matters – Here’s the bigger picture. By the late 1960s, satire had teeth, and politicians knew it. The law was clear. Comedians had wide First Amendment protection, especially after New York Times v. Sullivan. Legal protection is one thing, presidential pressure is another. That’s the tension I felt watching TV as a teenager. Could politicians take a joke, or would they try to silence the laughter? Half a century later, I think we’re still asking the same question.